SSH must be my favourite piece of software ever. It’s free, it gives you freedom, it’s simple to use yet powerful in the things it can do. It helps you to encrypt and secure your communication. It can do this in an universal way and for nearly every usage case. In this post, I want to show you 6 things you can do with SSH without too much hassle. SSH can do more than just serve as an encrypted remote session. Try the following examples for yourself and explore the power of the Secure Shell.

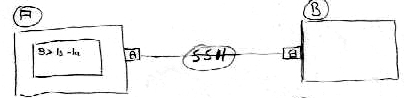

Thingy #1 – A secure remote shell

OK, this is the most obvious thing you can do with SSH and i bet most of you have already done it: Connect to a remote machine via a SSH-secured connection and type on it’s console to administer it.

This is very simple:

ssh user@box_B

This will connect you to Box B as user „user“. After having entered your password, you will be able to use BOX B’s console.

Sometimes you don’t want to connect to the remote machine for an interactive session, because you just want to run a single command on the remote machine. In that case you can just do a

ssh user@box_B command

This will connect to Box B as „user“, run „command“, show you „command“’s output and disconnect.

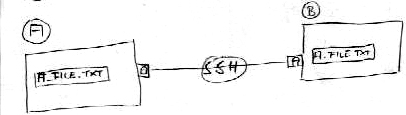

Thingy #2 – Copy files between your boxes

Great, we can administer a remote machine with SSH but we can also move data between machines in an encrypted and secure way. It basicly works like the standard „cp“ command, but it has got a different name: „scp“

scp /home/me/a_file.txt user@box_B:/home/me/

This will copy the local file „/home/me/a_file.txt“ on our Box A to „/home/me/a_file.txt“ on Box B.

It will work vice versa as well:

scp user@box_B:/home/me/b_file.txt /home/me

This would get the file „/home/me/b_file.txt“ and would put in into our home dir on box A.

Because „scp“ works like „cp“ wildcards are allowed as well:

scp /var/log/* user@box_B:/home/me/logsbackup

This would copy all of the log files from our Box A to „/home/me/logsbackup“ on Box B.

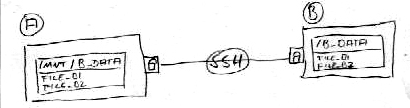

Thingy #3 – Mount a remote directory into your local file system

Sometimes it’s not enough to simply copy one or more files from one machine to another. Mounting a remote directrory into your local filesystem becomes super useful, when you want to work on the remote files with local programs. A good example for this would be working on a remote website. You can simply mount the web-directory from the remote server into your local filesystem and use all your fancy HTML-editors and image-programs on the remote files as if they were on your local harddrive. That’s where „sshfs“ comes in handy. The tool isn’t installed by default in most distributions but you should be able to find it in your repository. On Debian based systems just install it with:

apt-get install sshfs

After having installed sshfs you can start using it:

mkdir /mnt/b_data sshfs user@box_B:/b_data /mnt/b_data

This mounts the directory „/b_data“ from box B into „/mnt/b_data“ on your local file system. Now you can work on your remote files with local tools. When you are done, you can unmount the directory with:

fusermount -u /mnt/b_data

If the unmount fails, check if you have still open files in the directory or if you are still in that directory in some shell or Nautilus/Konqueror window.

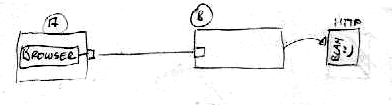

Thingy #4 – Surf the Web uncensored and anonymously from „critical“ locations

Corporate policies, fascist governments, internet cafés and other „unfriendly“ rules, institutions and places can give you a hard time, when you want to access the web in a secure and private way. Firewalls and proxies may block your favourite sites, log the sites you have visited, perform man in the middle attacks or can just give you a bad feeling. SSH is the solution for these problems. It offers you the possibility to use it as a web-proxy. You simply connect to your good old trusted box B and surf through the encrypted connection.

(Local Browser <-> Local SSH Proxy <-> SSH <-> Box B <-> Website)

Now nobody on your unfriendly local LAN can block or spy on your surfing session.

Sounds good? Great! It’s even simple to setup. SSH offers the „-D“ option to provide a SOCKS proxy on the local machine:

ssh -D 1234 user@box_B

You’ll have a proxy listening on localhost port 1234. Now you just have to setup your webbrowser to use the „SOCKS proxy“ on localhost port 1234 and all your surfing will go through Box B. You can check if it worked by visiting a website that shows your IP. http://www.whatismyip.com is a site that would work. If that site shows Box B’s IP-address instead of your local one, you setup everything correctly. A portable webbrowser on your USB-pendrive like Portable Firefox would make things even more cozy.

Thingy #5 – Encrypt the data traffic of your favourite local application or access services in LAN’s you couldn’t reach otherwise with SSH-tunnels

OK, we encrypted remote admin-sessions, copied files securely and even surfed the web in a private way. But SSH can do more. You can encrypt the traffic of every application that uses the TCP-protocol with SSH tunnels. Like with our SOCKS-proxy, we can tunnel other data through ssh, for example the traffic of our e-mail client. Lets say you want to pickup your e-mail while being in a „critical“ environment. Bad corporations / governments / script kiddies could read your email and even worse could sniff your e-mail password. SSH helps. The syntax for tunnels in SSH might puzzle your brain at first sight, but it’s not too hard:

ssh -L local_port:target_host:target_port user@box_B

for example

ssh -L 10000:pop3.mailprovider.com:110 user@box_B

OK, lets see what happened here. We told ssh to create a tunnel with a local (-L) endpoint at port „10000“. Everything that is put into our local endpoint goes first encrypted to our Box B and after that to „pop3.mailprovider.com“ on port 110 (which is POP3). You relay all data that goes into our local endpoint in an encrypted way via Box B to your E-Mail provider. In this example you would set the POP-account in your e-mail client to „localhost“ port „10000“. It doesn’t have to be e-mail. Any other application that uses a protocol utilizing TCP works as well. For example IRC, FTP, HTTP, IMAP, you name it…

in case you are running your own server-service on Box B, „target host“ can be Box B itself of course:

ssh -L 10000:127.0.0.1:110 user@box_B

Target host in this example is „127.0.0.1“ because it’s the target from Box B’s point of view. „127.0.0.1“ seen from Box B sure is Box B itself.

Tunneling can be useful to secure your services or to connect to services inside BOX B’s network. Lets say BOX B is in an intranet that has an interesting webserver on IP „192.168.0.77“ and you are unable to access that server from the outside. You just tunnel your way to BOX B and let BOX B forward you to the webserver:

ssh -L 10000:192.168.0.77:80 user@box_B

Now typing „http://127.0.0.1:10000“ into your local webbrowser will show you the homepage of the intranets webserver.

Thingy #6 – A tunnel the other way around

OK, this could have been part of „Thingy #5“ but to make things more clear i made an extra point for it. If you understood #5 this should be no problem for you. Here, you open up a „remote“ endpoint on Box B. Everything that goes in there is relayed encrypted to Box A (the one you are using at the moment) and after that to the target host.

ssh -R remote_port:target_host:target_port user@box_B

for example

ssh -R 10000:pop3.mailprovider.com:110 user@box_B

An e-mail client would set „box_B“ and port „10000“ as the POP3 server. BOX B would relay the traffic to BOX A through SSH. BOX A would relay the traffic to „pop3.mailprovider.com“ port „110“.

Useful commandline options for SSH

-c „Compress“

The „-c“ option in SSH compresses all traffic with gzip before sending it to the remote host. This increases the speed greatly with uncompressed data-types. It’s very useful for copying large text-files over SSH or for surfing the web with the „-D“ option. In general „-c“ never hurts, it just puts a little more pressure onto your CPU.

ssh -c -D 1234 user@box_B

-g „Grant Access“

The „-g“ option allows other hosts to connect to your local tunnel endpoints. If you don’t use „-g“ in combination with a tunnel, only your own localhost (Box A in the examples) may use the tunnel.

ssh -L -g 10000:127.0.0.1:110 user@box_B

-p „Port“

The „-p“ option is needed, if the SSH-server you want to connect to doesn’t run on the default port „22“

ssh -p 22000 user@box_b

-v „Verbose“

Add this option if you want to dive deeper into SSH. You will see many technical information while connecting to a remote host.

Further reading

I tried to keep this article as simple as possible to make it usable. There is a lot more to know about SSH. If you are looking for a more comprehensive read i suggest you check out these docs:

Daniel – I came across this article while searching for useful things to do with SSH. This is one of the best articles I have seen on the topic. Thanks for publishing it! I hope you continue to write.